By: Kelly Vaz Lima

A major issue throughout the holidays is waste. “Over 70 billion pounds of food waste reaches our landfills every year, contributing to methane emissions, wasting energy and resources across the food supply chain” said EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler. According to The Ecology Center, the United States sees a 25% increase in waste between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Eve. That’s 1 million extra tons of waste!

What does waste have to do with climate change and what can we do about it?

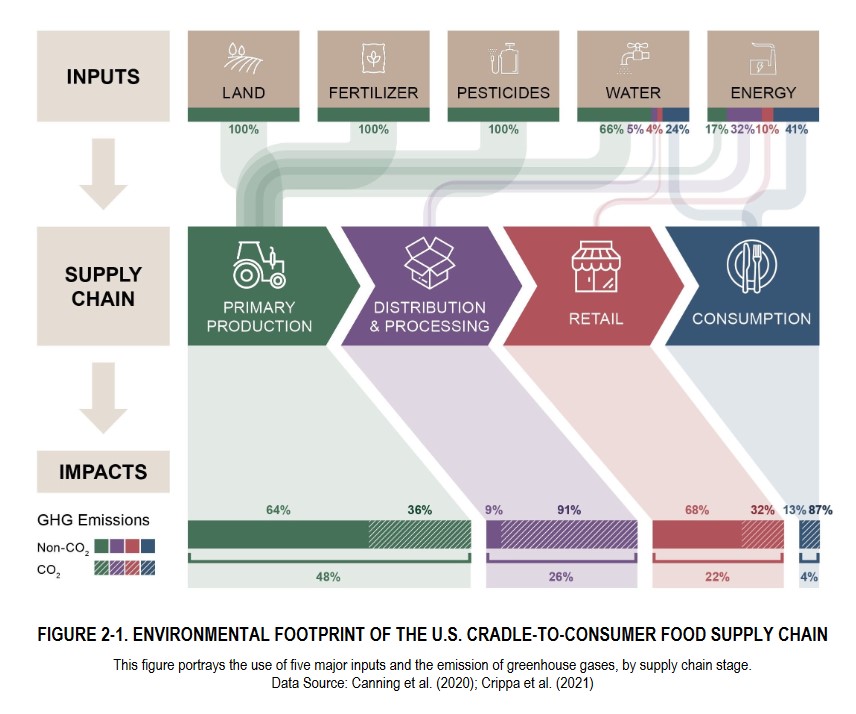

According to the World Wildlife Fund, global food waste contributes 10% of our global greenhouse gas emissions. When food is wasted, so are all the resources that went into making it. These resources include land, water, and energy.

During the primary production phase, land and water use is vital to growing crops and tending to livestock. National Geographic suggests that an area roughly the size of South America is used for crop production, while even more land—7.9 to 8.9 billion acres (3.2 to 3.6 billion hectares)—is being used to raise livestock. With the world demanding higher agricultural production, deforestation has accelerated immensely. Water is also largely used during the primary production phase. With the decline of water quality worldwide, this resource is becoming increasingly scarcer and needs to be conserved.

During the production, transportation, and decomposition process of food, an immense amount of greenhouse gasses are released. Food waste produces methane during its decomposition process that is over 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. According to the Environmental Defense Fund, methane has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide. Emissions are also produced by the transportation and refrigeration needed to deliver out-of-season foods. The distance food travels is often referred to as “food miles”.

According to the EPA, more than 35 million Americans lived in food-insecure households in 2019, and in 2020, people are going to food banks for their groceries in record numbers. By reducing the amount of food wasted, together we can protect human health and the environment.

EPA suggests the following food waste reduction tips:

- Create and stick to shopping lists.

- “Shop” the refrigerator and pantry first, so that food does not go to waste and shopping needs are reduced.

- Plan an “eat the leftovers” night.

- “Befriend” the freezer. Freeze extra food such as side dishes or meat.

- Reconsider food storage methods.

- Consider purchasing “imperfect” food.

- Consider sharing extra food with family or donating to a local charity.

- Purchase in-season food from local farmers.

- Compost; This is an extremely environmentally friendly way to add nutrients back into your soil!

How are we tackling food waste at Rutgers?

Emissions from Rutgers dining services constitute 20,500 tonnes of carbon dioxide. These are dominated by emissions associated with beef and chicken menu items. The Rutgers Climate Task Force estimated that a 25-30% reduction in food supply chain emissions could be achieved from menu changes, including up to a 20% reduction in the amount of meat in recipes, and including more plant-based foods on the menu. Rutgers is combating “food miles” by prioritizing local food suppliers for food procurement, especially seafood, chicken, fruits, and vegetables, when in season. The University is also exploring anaerobic digestion and/ or commercial composting within local communities.

The Dining Services and Food Vendors CAG is analyzing and reducing emissions from food production and transportation as well as food waste disposal. The GHG Protocol Product Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard helps calculate the emissions associated with a product and identify greenhouse gas reduction opportunities through its life cycle. Rutgers can then use this standard to measure the greenhouse gasses associated with the full life cycle of the products we procure, including raw materials, manufacturing, transportation, storage, use and disposal.